St Felix Church Felixkirk North Yorkshire

The Church

There is no known link with St Felix (felix = happy in Latin) who came to convert Sigbert, King of the East Saxons in 604 and was Bishop of Dunwich and East Anglia from 630 A.D. The old name of the village gave way to that of Saint Felix, the patron saint.

Before 1175 the church seems to have consisted of an aisleless nave and chancel which was probably apsidal. In the last quarter of the 12th century the aisles were added and the two great pillars were built to carry the arches which replaced the earlier north and south walls of the nave. Later the eastern portion of the chancel was replaced by a rectangular sanctuary. The ground plan remained in this form till 1859 until substantially rebuilt in 1860 by William Hey Dykes. The present, very beautiful church with its unusual rounded apse owes much to Dykes' genius. Canon Johnstone, younger son of Lord Derwent, and his curate, Revd. W.A. Norris, raised £1,600 for the restoration.

Tour of the Church

Entering through the modern porch one can see the basin of an early font which is believed to have come from a long-disappeared church in the neighbouring village of Sutton-under-Whitestonecliffe. The font in the church is modern. Looking up at the south-west corner of the inner roof of the nave, almost hidden by the first roof truss, it is possible to see the quoins of the south wall of the nave of the pre-1175 church. The tower is later than the early church, probably 16th century. Under the nave walkway is a cast iron stove and a duct for the hot gases which led up to the chancel steps and thence to a flue to the north of the pulpit. This extremely effective heating system had to be abandoned when no-one could be found to stoke the stove; but its passing is much regretted in cold weather!

The chancel arch is Norman in appearance but opinions differ on how much of it dates from the pre-1300 church and how much from Dykes. The columns and capitals, at least, are generally agreed to be original. In both walls of the quire are lancet windows dating from the pre-1175 church. The blocked doorway in the south wall is said by Bogg to have come from an earlier door in the south aisle. Two large iron crooks can be seen at the top of the chancel arch columns. These once supported curtains known as a Lenten Veil which hid the sanctuary from the congregation and possibly kept the draughts away from the knights!

The next arch, separating the quire from the apse, was rebuilt by Dykes using some earlier material and is Norman in conception. The walls of the western part of the apse are straight and slightly convergent and lead into the interlacing Romanesque arcading which dates from Dykes' restoration. The present apse is said to have been built on, or in conformity with, the foundations of the original apse. In the north wall of the apse, in the straight portion of the wall, is a two-light window dating from pre-1300 and containing portions of mediaeval glass. The arms on the four escutcheons are of Walkingham (upper left), Cantilupe (upper right), de Roos (lower left) and Elsley (lower right). The first three figure prominently in the early history of the church and the Elsley family lived at Mount St John in the last century. In the tracery at the top there is a representation of the Trinity. Under the window is the effigy in stone of a Crusader knight and, on the south side, a contemporary effigy of a woman, assumed to be his wife (see below for history of this couple).

Returning to the south aisle, there is a fine example of today's stained glass in a window in memory of Brig. Walker, last of the three generations of Walkers at Mount St John and Ravensthorpe in nearby Boltby

The Arms and the Figures

Authors differ over the identity of the two effigies. One suggestion is that they are of the de Roos family, lords of Helmsley and owners of the fortified manor at Old Ravensthorpe between Thirlby and Boltby within this parish. However it is more generally held that the woman is Eva de Boltby, a local heiress, who had three husbands. The first, John de Walkingham (d.1284), the second Richard Knut of Kepwick who must have died not long after and, thirdly, William de Cantilupe, Lord of Ravensthorpe (m. Eva 1292, d.1309). As you have seen, the arms of de Roos, de Walkingham and de Cantilupe all appear in the apse window but those of the short-lived Knut do not. A further confusion arises over the lady's name; possibly Lady Joan or Lady Eva of Boltby (d.1309), perhaps of the de Roos family herself. The de Cantilupes died out in 1391. The old manor was replaced by an eighteenth century house on the west side of Boltby where part of the Walker family lived until the 1940s.

The Bells, Tower and Organ

At a guess the tower is 16th century and used to have a gallery and internal ladders for access (look at the stonework where the beams rested). When the Walcker organ (German) was plumbed in, literally, for it had an hydraulic action, in March 1888 the north aisle roof was raised and the exterior spiral steps to the clock and bell chamber were added.

The treble and two other bells were made and added in 1898 to the three already there which date from 1620. Of these the tenor bell is 8 cwt and 36" in diameter, inscribed "All glory to God on High to all Eternity, 1656". The fifth bell is 6 cwt and inscribed "Jesus be our Speed, 1620".

Finally, in the churchyard, there is the tombstone of Hannah Cornforth, who died aged 21 in 1853, with the inscription (readable in 1859 at least):

Twenty years I was a maid,

One year I was a wife,

Eighteen hours a mother,

And then departed life.

See, too, the 12th century knight's headstone outside the vestry window.

Other information and points of interest for reference:

The Walker family were iron founders from Sheffield and cast the cannon for the Victory and other R.N. ships during the Napoleonic Wars.

Other effigies of knights to be seen in conjunction with the one here: Robert de Moreby, 1286-1336, at Stillingfleet is in exactly the same style (but more an apprentice's work than our rather de luxe version); both carved at the same workshop at Skipton in the old West Riding; also Nicholas de Cantilupe of the 13th century at St Mary's, Ilkeston, Derbyshire.

A tomb of a member of the de Roos family, dating from the 14th century, is in the round church of the Temple, Fleet Street, London.

De Roos bougets (heraldic water vessel devices) are to be seen clearly on the London effigy, on Helmsley Castle, on the gatehouse of I<irkham Priory, in the glass of York Minster and Trinity Church, York. (No doubt a member of the family was prudent enough to have a flask of water with him and, refreshing his king after a battle, earned his title, still part of the Earls of Mowbray's style.)

The Calendar Close Rolls 1256-1419 mention Roger de Mowbray and Nicholas de Boltby; summoned to do the king's business and fight in Wales versus Llewellyn ap Griffin, or in Scotland if the Nevilles required them. Other references are mainly legal to do with the tenure of Boltby, Thirlby and Ravensthorpe through inheritance, escheatage, default or royal pardon (1 391), mentioning Nicholas' son by Philippa 14th December 1272, Adam and his late wife Annora, 1282, along with relations of the de Cantilupes, namely John de Hastings, Earl of Pembroke (some of which family have effigies in the Temple Church from 1219).

St Felix. A small cameo of him is in the glass by the north chancel door at Blythborough, Suffolk. Dunwich, just to the east, was a prosperous mediaeval harbour and city, which now lies two miles out under the North Sea. It was a rotten borough afterwards.

A.J.N.

Bibliography:

William Grainge, Vale of Mowbray, 1859.

Edmund Bogg, Richmondshire and the Vale of Mowbray, 1906.

Nicholas Pevsner, Yorkshire - The North Riding, Penguin 1966.

Archives at County Hall, Northallerton.

Acknowledgements:

Miss Ruth Mitchell

Rev. P.R.A.R. Hoare

Major E. Chetwynd-Stapylton - Churchwarden.

The Organ in St Felix Church, Felixkirk

by Duncan Mathews

The development of English organ building during the nineteenth century is increasingly well documented, though much research remains to be done. Several large firms came to dominate the scene, each pursuing their own tonal ideas; continental influences were a significant factor, but were generally assimilated into a recognisably English style. At this time many English firms were successfully exporting their instruments; most of these organs, however, were sold to the colonies, and relatively few reached mainland Europe.

In the reverse direction, with the exception of substantial instruments by Schulze and Cavaill & Coll, the organs that reached these shores were smaller two-manual instruments by builders such as Walcker, Anneessens and Mutin, the successor to Cavaill & Coll. It is interesting to speculate on the background to such organs being built in Britain; presumably some influence came from local musicians who were well travelled, but this does not fully explain the large number of organs built by Walcker, mainly in Scotland, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Whatever the reasons, their arrival must have caused a stir. Tonally quite different to the English organ of the day, and employing unfamiliar types of action, they must have been regarded with some awe, particularly by those who had to tune and maintain them. During the present century many of these instruments have been "improved" and changed out of all recognition. On occasion such work was doubtless undertaken because the sound of the organ did not fit in with the fashion of the day; the Walcker voicing being, I am sure, rather too bright and keen for general acceptance during the 1920s and 30s. Their actions may also have been thought too complicated and difficult to work on (though certain English creations of this period could well fall into the same category!). The archives of Harrison & Harrison bear witness to the problems encountered by English organ builders working on Walcker actions. According to a report written in 1926 by one of our men, a large instrument in Yorkshire had been "given up on" by a local builder, and two others would not entertain taking it on. Our man reported considerable problems with the organ, fault correction being made all the more difficult due "to all the action boxes being marked in German and one cannot tell what is what".

It is therefore unusual and gratifying to find untouched examples of Walcker's work today, and we at Harrison & Harrison are pleased to have been involved with the restoration of two such organs by Walcker in recent years: the first built in 1903 for Lochmaben Parish Church, Dumfriesshire (see The Organbuilder 1995), and the second the subject of this article. Built in 1890 for St Felix Church, Felixkirk, in North Yorkshire, it is an organ of considerable size and complexity for a small village church.

The organ is built into a shallow chamber at the west end of the north aisle, speaking east. The Great Organ is on the first level, with the Pedal divided at either side. The Swell is on two levels above the Great. This very tall, shallow layout is excellent for sound but makes tuning and maintenance very difficult.

The console is slightly detached, and the organist sits with his back to the organ facing east. In Walcker's original specification, the console was to be sited in the chancel some thirty-five feet from the organ; there is no evidence that this ambitious plan was ever put into operation.

|

Specification of the Organ in St Felix Church, Felixkirk |

||

|

Great Organ Bourdon 16 Open Diapason 8 Viola di Gamba 8 Rohrflûte 8 Salicional 8 Principal 4 Rohrflûte 4 Mixtur 2 2/3 |

Swell Organ Lieblich Gedacht 16 Geigenprincipal 8 Lieblich Gedackt 8 Dulciana 8 Voix Céleste (tenor c) 8 Geigenprincipal 4 Flauto Traverse 4 Piccolo 2 Trumpet 8 Oboë 8 |

Pedal Organ Violonbass 16 Bourdon 16 Violoncello 8 Couplers Swell to Great Great to Pedal Swell to Pedal Pedal Octave Octave Coupler for Swell Tutti Coupler |

| Manual Compass 56 notes Pedal Compass 30 notes | ||

The stop names that appear on the knobs are almost as written in Walcker's specification book (pages 356 ff); a copy of this entry was kindly supplied by the Walcker firm.

Clearly an effort was made to accommodate their English customers: however, the pipes themselves are marked in German. The stop jambs are terraced in two rows at either side of the keyboard. The knobs are turned from mahogany, and the stop names appear on round porcelain discs above each. Each department's labels are colour coded; the Great being white, the Swell lilac and the Pedal light green. This is extended to the coupler labels which bear both colours of the departments to be coupled. The couplers are operated by pairs of buttons set into the Great keyslip, one each for on and off.

There are no pistons or combination pedals. In their place are four blind preset combinations. The system is highly ingenious: the combinations are set by punching holes in a cardboard strip which is inserted below a grooved wooden block to the left of the keyboard. Sliding this block produces the combination. By varying the layout in the cardboard strips, the presets can be made to operate the whole organ or only one department (without overriding stops already drawn).

The casework is an impressive piece of craftsmanship; constructed of oak, with a natural finish, it dominates the north aisle. The swell-box, veneered in oak to match the case, is clearly visible above the front pipes, and the total height of the organ is well over 25 feet. The front pipes are of tin.

The construction of the organ bears all the hallmarks of its era. In broad terms it is very similar to the organ at Lochmaben, but in detail it is quite different. Everything is massive and solid; no use of thin or flimsy materials here, all internal woodwork is solid pitch pine and heavy in weight. In many ways its internal construction is rather primitive, and it is obvious that major manufacturing changes were made by Walcker between the building of this organ and that at Lochmaben, which has much more of a factory-made look to it.

The action is charge-pneumatic throughout, working cone-valve sliderless chests. The lead action tubing is large bore, and each tube is run individually; where an English organbuilder would have used tube trays, horizontal tubes are supported individually by iron hooks.

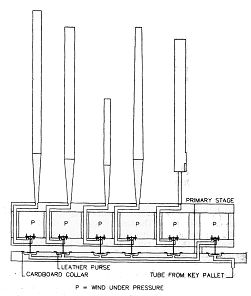

The actions have all been fully restored. They are based on purses rather than motors as used later at Lochmaben. A great advantage of purses is their ease of renewal; each purse is separately leathered onto a thick card collar before being glued into position on the board. (See Diagram 1). All the pipework stands in ranks above individual stop chambers that are flooded with air by a ventil when a stop is drawn. When a note is pressed at the console, acharge of air inflates a primary purse at the soundboard which works a valve; this in turn causes a further charge of air to inflate all the individual purses for that note, there being one per stop. These work the cone valves that supply the pipes, but no pipe will sound unless a stop is drawn.

All coupling is charge-pneumatic. When the coupler is off, flat springs hold a strip of leather in position sealing the windway. When the coupler is on, a pin, lifted by a rectangular motor, lifts the spring clear of the leather strip allowing a charge of wind to pass. (See Diagram 2).

The double-rise reservoir, placed at the bottom of the organ, was in poor condition and has been releathered. The woodwork was covered in blue sugar paper in the style favoured by Walcker, and this has all been renewed. An interesting feature of Walcker organs is their use of local bricks, neatly wrapped in blue paper, as reservoir weights; no doubt a more economical approach than shipping iron weights.

The two concertina trunks and three concussion bellows were also releathered, and their paper covering renewed.

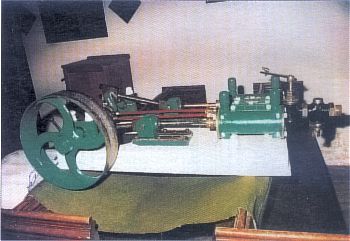

The reservoir has three feeders. This is no evidence that this organ was ever hand-blown: the feeders were originally linked to a water engine sited below the organ floor. This method of raising the wind was superseded by an electric blower around 1964, and the water engine was forgotten. Rediscovered during the restoration of the organ, the engine was removed from its pit and cosmetically restored by one of the churchwardens; it is now on display within the church. Interestingly it is of English manufacture; Walcker's specification indicated that they would prepare for this only. Sadly, today's water pressure is thought too low to allow the water-engine to be brought back into use; the feeders have been retained but not releathered.

Diagram 1. Section through a Waicker cone valve soundboard (closed position)

Diagram 2. Waicker charge pneumatic coupling.

A tremulant was added to the organ some time early this century. This was controlled by exhaust-pneumatic action from a single stop tab at the console, the machine itself being awkwardly sited within the organ. It was felt that this was an inappropriate alteration, and it was discarded.

The sound of the organ is colourful, incisive and very exciting, and we have taken pains to preserve it without alteration. Cone and roll tuning has been retained throughout. The voicing is characteristically vigorous; the onset of speech is somewhat explosive, answering to the design of the action.

The principals and strings are keen and bright, with a forceful Mixture on the Great. The fiery Swell Trumpet is heavily mitred to fit into a low area, the mitres being at right angles rather than gently turned in the English style. The Swell Oboe 8ft is a later stop, possibly dating from around 1920; it is likely that this was a substitute for the original Oboe that appears in Walcker's specification, something a little more refined being thought desirable at this time. No attempt has been made to change this stop, it being accepted as part of the organ's history.

The restoration of this remarkable organ was a great undertaking which made considerable demands on all concerned. The results have amply justified all the effort involved. The parish rallied enthusiastically to the cause, and generous support was obtained from the Heritage Lottery Fund. Encouraged by the Fund, the church now has a regular musical programme: the first event was a recital by Dr Francis Jackson on Sunday 4 May 1997 to mark the restoration of the organ. It is good to know that the rejuvenated instrument will play its part in the musical life of this beautiful part of North Yorkshire for many years to come.

Duncan Mathews is works manager at

Harrison & Harrison Ltd Organ Builders St John's Rd Medowfield Durham DH7

8YH 0191 378 2222

This article appeared in Nov 1999 "Organist's Review"